The Problem with Solving Problems

A Strange Note in Oṣù Ẹ̀bìbì*

Years before plastics became our unavoidable companion, the awe-inducing mammals, Elephants, involuntarily provided us with ivory from their dentine-rich tusks that have functioned as instruments for digging holes, gathering food, intimidating rivals, among other needs – some of which have persisted for millenniums.

Loved for its durability and versatility, Ivory – which is most present on Elephants residing in Africa – has served humans for numerous purposes, including in the replacement for teeth, design of jewellery, and development of piano keys, etc. As access to transcontinental transportation expanded, so did an insatiable demand for the use of Ivory in human-operated products.

‘One of the biggest uses,’ as captured by Susan Freinkel, in her book, Plastics: A Toxic Love Story. ‘was for billiard balls. Billiards had come to captivate upper-crust society in the United States as well as in Europe. Every estate, every mansion had a billiards table, and by the mid-1800s, there was growing concern that there would soon be no more elephants left to keep the game tables stocked with balls. The situation was most dire in Ceylon, source of the ivory that made the best billiard balls. There, in the northern part of the island, upon the reward of a few shillings per head being offered by the authorities, 3,500 pachyderms were dispatched in less than three years by the natives. All told, at least one million pounds of ivory were consumed each year, sparking fears of an ivory shortage.’

With a potential threat to the existence of Elephants, humanity began its quest for newer ways to feed its vast needs without harming natural elements. The journey toward this became promising when, in 1862, the metallurgist, Alexander Parkes, developed Parkesine, a flexible material made from cellulose treated with nitric acid and solvents like alcohol. Parkesine paved way for the development of bakelite (the world’s first synthetic plastic), and further understanding of polymers (a substance contained in every living organism) catapulted a staggering number of chemical and plastic innovations from the early 1900s.

Although plastics are relatively new, the concept of being freed from the confines of the natural world isn’t. ‘The Victorian era,’ Freinkel observed, ‘was fascinated with natural plastics such as rubber and shellac. They saw in these substances the first hints of ways to transcend the vexing limits of wood and iron and glass. Here were materials that were malleable but also amenable to being hardened into a final manufactured form.’ Through remarkable advancements, the career of plastic as ubiquitous materials that now engulfs our daily lives has expanded across different fields of life, finding application in our homes, health facilities, gamepads, and a long list of spaces ventured by humanity.

Despite its miraculous job at, in part, preserving the Elephant species and enabling the invention of numerous utilities, plastic’s reputation has been called into question in the past decades. Freinkel observes that ‘most of today’s plastics are made of hydrocarbon molecules—packets of carbon and hydrogen—derived from the refining of oil and natural gas.’ Through their quality of durability, synthetic plastics are materials that transcend the wrinkles of time. Thus, debris from plastic materials created as early as the early 1900s continue to plague our water bodies, harming a variety of sea dependent creatures. Also, certain additives in plastics have become threats to our already mortal humanity, as they disharmonize our long-term health.

In essence, this material created to solve the problem of Elephants’ extinction has caused newer problems affecting other life forms. And while modern innovators are turning to plant cellulose – the raw material for the earliest plastics – as a solution to the hazardousness of plastics, the history of plastic exemplifies the problem with solving problems, which is this: newer problems ultimately arise from our attempt at solving an existing problem.

Plastics are only a single example in a collection of references. Every human venture is essentially pursued with a desire to solve a problem. The creation of music, for instance, might be done to solve the problem of self-expression, social and financial status, or social issues. As their creation passes through waves to reside in the heart of other humans, it has the potential of being problematic to the beliefs and tastes of another. A piece of music, as much as it elevates our spirit, can also incite devastating wars between groups.

This desire for solving a problem is also present in our daily activities. We bath to solve the problem of uncleanliness – this potentially creates the problem of water loss. We eat to solve the problem of hunger, creating the problem of a species’s extinction. We primarily put on footwear to protect our feet and, in doing this, make room for problems like tired feet or inability to flee danger due to tight shoes. With an abundance of references to the making of problems from solving other problems, we are made to reflect on the cause of this problem transference. Why does solving one problem result in another problem?

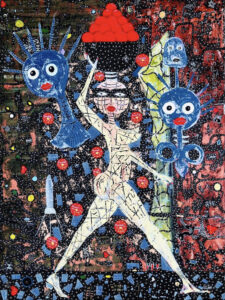

Taxi Brousse by Cameroonian Artist, Abdias Ngateu

Problems are an inevitable part of the human experience. As reflected within the concept of the cyclicity of emotions and how it can enable us live through hardship, life is a web of suffering and problems result in emotional elements of suffering like sadness and happiness, which are but temporary. These elements, throughout humanity’s presence on earth, have been a vital ingredient for the survival and evolution of our species. We innovate because of problems. It is – as we are currently witnessing through the devastating arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic – during times of crisis that the world most shifts to birth new ways of life. This use of problem as a tool for survival extends to animals and plants that continuously evolve in their approach of avoiding danger: it touches and recreates the individual self, using experiences, emotions, and logic as pivoting tools. As Rainer Rilke eloquently advised on the temporality of experiences, we all ‘have had many and great sadnesses, which passed… Consider whether these great sadnesses have not rather gone right through the centre of yourself? Whether much in you has not altered, whether you have not somewhere, at some point of your being, undergone a change while you were sad? … Were it possible for us to see further than our knowledge reaches, perhaps we would endure our sadnesses with greater confidence than our joys.’

A problem also results in another because everything on our planet is intricately connected. So, when a shift occurs in one area, it causes change in another. The connectedness of all things has long been contemplated by philosophers and the practicality of science which, recently, has explained this connection using the ‘resonance theory of consciousness’, an observation made by the scholars, Tam Hunt and Jonathan Schooler. Building upon the pillars of biophysics, and neuroscience, the lot suggest that resonance—another word for synchronized vibrations—is at the heart of not only human consciousness but of physical reality more generally.’ They agree that ‘vibrations, resonance, are the key mechanism behind human consciousness, as well as animal consciousness more generally. And they are the basic mechanism for all physical interactions to occur.’

A more simple representation of this connectedness is the food chain. As noted within the educational piece of the free – and adequately rich – learning platform, Khan Academy, ‘a food chain is a series of organisms that eat one another so that energy and nutrients flow from one to the next. For example, if you had a hamburger for lunch, you might be part of a food chain that looks like this: grass > cow > human.’ This order of events in our ecosystem is formed by the flow of nutrients and energy between organisms at different trophic levels (which describes the position of an organism in the chain). When harm befalls an element within this cycle, it ceases to function as it should and affects the normalcy that governs other elements within the system. We all depend on each other to maintain a delicate balance in the universe. In this way, not only is are we directly affected by an event, but it changes the shape of another’s existence.

The problem with solving problems arises from a combination of the inevitability of suffering, our connectedness as humans, and because, try as we may, we can’t foretell the future as it would be. As Paul Deane expressed within the digital pages of Raidió Teilifís Éireann, ‘we tend to assume the future will be better and comfortably buy into utopian visions. This is an inherent part of the human collective; believing in a better future is good for social cohesion.’

Although – by calling on the weapons of data – we can predict the future, predictions can yield a wrong result. Predictions, which are formed by gathering our experiences and picking knowledge from the past, merely offer us a sense of what could be. It does not specifically state how it would be. So, challenged by these uncontrollable factors that determine the movement of problems through several spaces of existence, can we solve the problem with solving problems?

Miss Campbell by multi-cultural artist, Henri Abraham Univers available for purchase on Artsy.

As with several natural components of life, the road toward solving the problem of problems is no linear path. The thing to do is not avoiding a potential problem but, perhaps, developing systems that would enable solving future problems. Systems prepare us for the brunt of both registered and unforeseeable problems. A system for dealing with grief, as penned by Seneca in a letter to his grieving mother – and drawn from an expanded text in a vital approach to managing hardship – is preparation. Seneca advises us that, ‘those who have prepared in advance for the coming conflict, being properly drawn up and equipped, easily withstand the first onslaught, which is the most violent.’

Drawing from James Clear’s brilliant observation on establishing habits, systems for addressing the problem of habits encompass approaches like environmental design, refinement of one’s mentality, performing habits in bits, among other ingredients. And a system for dealing with problems of innovation could be the development of human capacity through investment in people and expanding the possibilities through which we can innovate for that potential problem.

Having understood the connectedness of humanity, empathy is additionally useful for managing the persistence of problems. Empathy provides foresight because it drives us to consider being as another. And when we can become something/someone else for a second, it becomes easier to understand the fragile defining constituents of things/people and to pursue actions with the armour of intentionality. But, as Dejamarie Crozier brilliantly revealed in Questioning Advocacy – in an episode of the Strange View Podcast –, impact does not always match intention. Drawing from her years of labour in social work, she expresses that ‘a lot of the time we live our life so well-intentioned that we think that we’re not, it’s not possible for us to make a mistake.’ She goes on to propose an effective remedy to falling prey to this bias, urging us to ‘live our lives intentionally, but be willing to look in the mirror and be honest with ourselves. Was your impact what you had initially intended it to be or was your impact the opposite of that?’

Although we might not be able to solve future problems through a foretelling, the message of empathy reminds us, as James Baldwin did, that ‘the interior life, and the intangible dreams of people have a tangible effect on the world.’ And when in the presence of a problem created by the dealings of the past, it’s worth remembering that future innovations will always challenge past assumptions, and the present quickly becomes the past. We are thus called to be mindful of imagining that a solution created today will have no negative effect in the future.

Problems, as reflected within this digital page, are an inevitable part of our existence, fostering the survival and evolution of our species. But, should we have to live through pain before we become better or evolve? We would naturally want ‘no’ as a response to that question but here is the thing; this individual self-shifting through times of pain or the collective group innovating during times of crisis predates our understanding of it. Although I do not subscribe to the notion that a person must live within the confines of pain to turn on the button of creativity, I believe that, as the American writer, Eric G. Wilson carefully exposed, ‘to desire only happiness in a world undoubtedly tragic is to become inauthentic, to settle for unrealistic abstractions that ignore concrete situations.’

1 Question for You

Do you have a system for solving problems?

As you think through this question, here’s what you should read next: Visit the pages that explore the fruitfulness of hardship, read an exert of Freinkel’s book detailing a brief history of plastics, and exit with a venture into the world of our mighty earthly companions, Elephants.

*Oṣù Ẹ̀bìbì is the Yorùbá word for the month, May. Yorùbá is a Kwa language, which belongs to the Yoruboid group under the Niger-Congo phylum. The language is spoken natively by about 30 million people in Nigeria and in the neighbouring countries of the Republic of Benin and Togo.

@etashelinto

@etashelinto