All This Talk About Purpose

A Strange Note in Asaramaa*

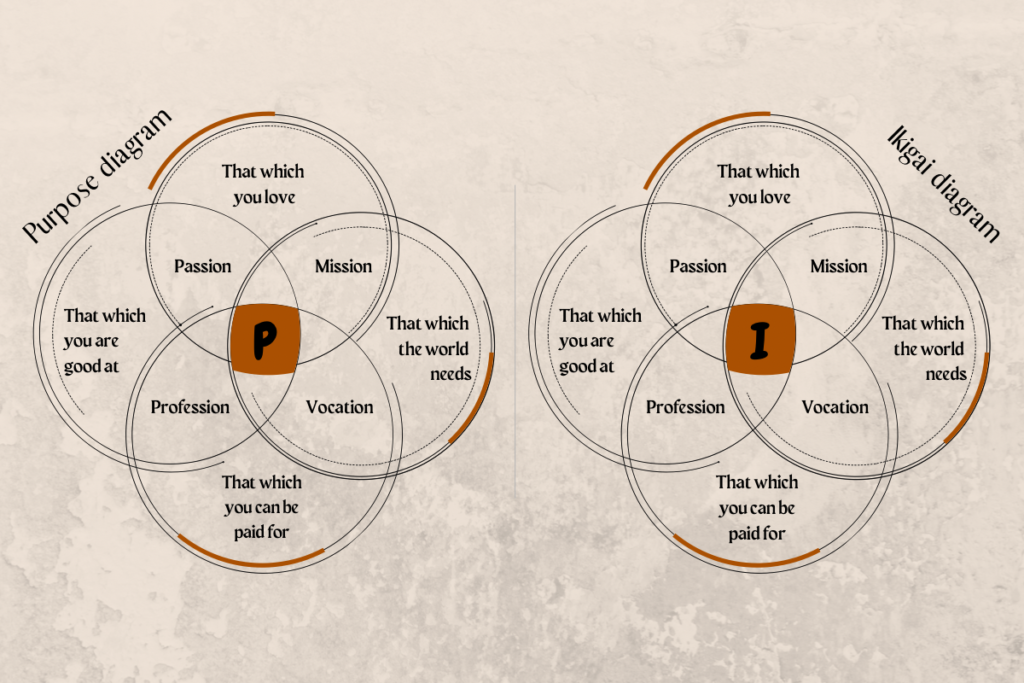

In 2014, Marc Winn, an entrepreneur, discovered ikigai in a Ted Talk by Dan Buettner, who spoke about the blue zones — local communities inhabited by beings that outstrip life expectancies to live beyond a century, in good health. Ikigai is a Japanese practice, an approach to life loosely translated into English as a reason for being. Winn, like many of us, lived in search of life’s meaning and his place in it. And so, having witnessed a new way of life that administers tranquillity, he merged it with the purpose diagram, writing that ‘Your ikigai lies at the centre of those interconnecting circles [in the purpose diagram]. If you are lacking in one area, you are missing out on your life’s potential. Not only that, but you are missing out on your chance to live a long and happy life.’

Reading his words, we’re at first intrigued by the purpose diagram and its elements. We want to know where we’re lacking because happiness is, after all, a state of self worth possessing, and we are beings puzzled by why we’re here. But we’re also forced to ask important questions about it all: What is the purpose diagram? Why merge the purpose diagram and ikigai? Should a diagram (which, I must mention, resonates with many people) dictate whether or not we’re missing out on our life’s potential? What does it even mean to discover our life’s potential or find our purpose in life? And, very important, do we need to have found our purpose to live a happy life?

An Origin Story

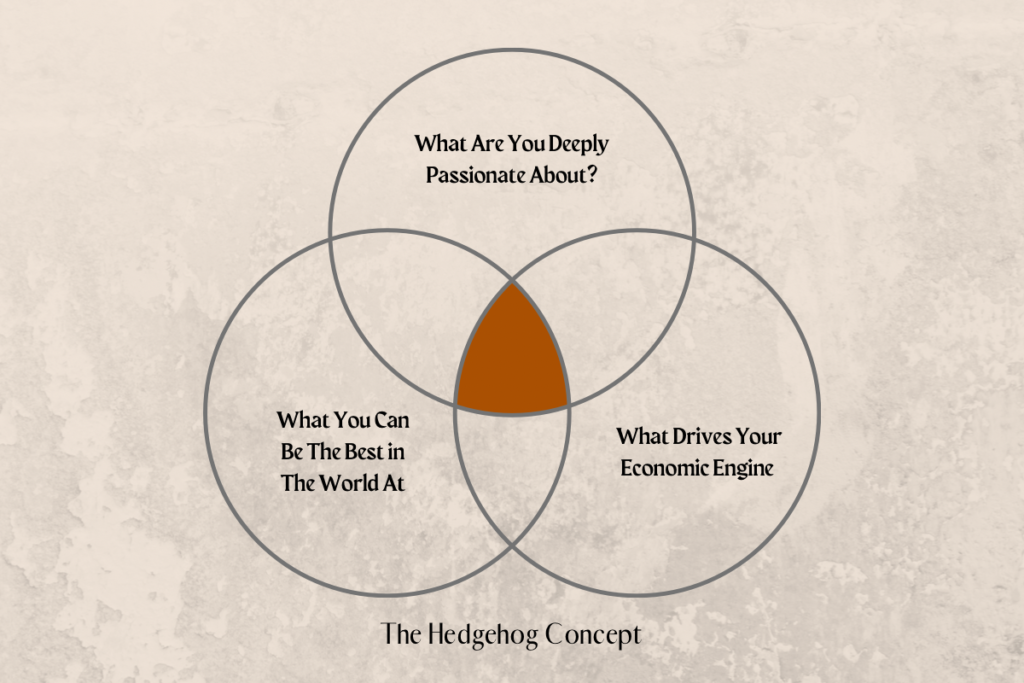

In his 2001 best seller, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap…And Others Don’t, Jim Collins introduced the Hedgehog Concept, which is based on an ancient Greek fable about the fox and the hedgehog. The fox, in the fable, attacks the hedgehog with a myriad of strategies, but the hedgehog — poor-sighted and slow-paced — simply defends itself by curling into a ball of spikes. Collins essentially argues that companies should unearth their edge and focus their efforts on it. ‘The good-to-great companies,’ Collins notes, ‘understood that doing what you are good at will only make you good; focusing solely on what you can potentially do better than any other organization is the only path to greatness.’ He further assembled a Venn diagram for the Hedgehog concept, portraying that, to be a Hedgehog, companies must engineer their work around passion, substance, and a vital source of financial wealth.

The Hedgehog concept promises market relevance and business success. It’s no surprise, then, that it soon won the hearts of entrepreneurs and was largely modified and renamed the Sweet Spot model as it entered the coaching sector and other industries. One of its most notable modifications was done by Andrés Zuzunaga, an astrologer and investigator of natal charts. Zuzunaga introduced a fourth circle to the Hedgehog concept, forming what would become the purpose diagram, which was further renamed the ikigai diagram by Marc Winn.

The purpose (or ikigai) diagram attempts a holistic approach to living. It tells us that we must do what we love, what we’re good at, what we can be paid for, and that which the world needs, to find our purpose. And only by finding our purpose are we ushered into the realm of a long, happy life. This call is comforting, more so in a world that, more often than not, requires us to reduce our interests to hobbies and prioritise affairs with monetary promises. We are nourished by doing what we love, satisfied if good at it, validated when paid for it, and touched by a sense of enrichment when it becomes a tool for the world’s needs — at least that which we can alleviate. Still, looking at the purpose diagram, we can’t help but wonder why we must do so much to live wholly. We can’t help but enter the doors of purpose to ask its meaning and know whether it is indeed a thing to be found, and, having found it, if it guarantees us a full, rich life.

Longing by Deborah Segun.

The Purpose Call

Back in secondary school, x was a big mystery to be found. It was exposed on chalkboards, yet hidden in my teacher’s frustration at the ninety-five of the class that couldn’t play his game of hide and seek. It was openly explored by the beloved five, if not one percent that grasped its axis, yet lost in my poor foundation of mathematics. It was declared easy, yet always required a roadmap that many of us had a hard time deciphering. And that’s a truth worth holding: maths is rich with roadmaps, formulas that, if diligently followed, would often lead to x.

The purpose call attempts a formulaic approach to living a happy life. It says: to find happiness, we must find our purpose, and to find our purpose, we must do this and that and that and this. But why are we so unhappy here anyway? Life is synonymous with uncertainty and we have a hard time navigating the unknown. Our default (and collective) solution to this insecurity has been to gain a sense of control through practices like science, culture, religion, productivity, etc. And so elements like the purpose diagram act as an assuring framework for living a happy life, even though the formula for happiness — if at all it has one — is as uncertain as life itself.

Life is fluid, and the purpose call does not account for that. It forces us to seek happiness as a reward only attainable by doing; to keep busy, prioritize capitalism, live outside ourselves, and centre the value of life around work. But happiness, like other states of self, is temporary and what we call purpose is a result of our (often painful) experiences. Two children neglected and abused at home might grow to find families elsewhere; one with humans that aid their healing, the other in a circle that teaches them anger as the only true response. Now adults, the former’s purpose likely becomes to ease the pain of others abused, while the latter finds their calling in breaking other selves. Our experiences are often limited by environment, often moulded by the behind-the-scenes workings of chance, often walled by our perspectives, reactions, and responses. The purpose call does not acknowledge that we are beings with very little experience of the world, limited by what we know — which, historically, is not a lot; we are beings meeting life at different stages of understanding, beings with ever-changing experiences and desires. It does not account for the possibility that our purpose is not ours to know, and maybe life becomes richer when we give up our search for why we are here.

A Moment of Stillness by Deborah Segun

Still, A Reason for Being

Ikigai is a core principle for life among the Okinawa people, a local Japanese community governed by simplicity and true friendship. It is a nuanced concept and, as Nicholas Kemp clearly observed, not a ‘sweet spot of doing something that you love, that you are good at, that the world needs, and that you can be paid for. It is a rich spectrum where you can find ikigai in the realm of small things, in the practice of a hobby, in your roles and relationships, and by simply living your values. It is something easily achievable, not a single formidable life goal that might take us years to achieve as represented by the Westernised version [in the purpose diagram].’

There’s an emptiness that follows seeking and not finding; a void unlocked by thinking that one has not found why they’re here; an open wound that blinds us from truly being here and experiencing the wealth of life. How about a life lived from a place of self-presence instead? An uneasy outlook in a culture that is both fast-paced and centred around work, I know. But by doing, we forget to live; to stay aware of what brings us calm and, once aware, spend time with it, be present with it, feel no rush with it, no need to capitalize on it; live life from that centre rather than chasing the long arms of purpose.

Reflecting on silence and its veiled potency in our lives, David Whyte, in Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words, observed that ‘Reality met on its own terms demands absolute presence, and absolute giving away, an ability to live on equal terms with the fleeting and the eternal, the hardly touchable and the fully possible, a full bodily appearance and disappearance, a rested giving in and giving up; another identity braver, more generous and more here than the one looking hungrily for the easy, unearned answer.’

We don’t need to be skilled painters or dancers or gardeners to find calm in such activities. We don’t need the world knowing how excellent we are at fishing or hiking or being a parent to feel nourished by them. We may or may never uncover what we deem a calling, and it matters less that we do than stay present here. Because the world moves and we move too. It reveals and we’re revealed too. It unfolds and unfolds and shows us over and over again that we are elements of life’s fluidity.

The Big Question

Reading more on Ikigai, I discovered the mismatch between its pictorial portrayal and what it truly means. It got me thinking about semantic change and the effect of language contact. But it also got me curious about our culture of finding purpose and what it means to live a rich life.

As you think through this question, here’s what you should read next: On life and its meaning, and why everything is so uncertain. If you’d like to explore the roots of the popularized Ikigai diagram, here are some additional materials: Marc Winn on Ikigai, Dan Buettner’s TED Talk on the blue zones, Nicholas Kemp and Lauchlan Mackinnon on the history of and problems with the Ikigai diagram.

*Asaramaa is synonymous with the English word, seven. It is of the Bedawi language, a Cushitic language spoken by over 2 million people across Sudan, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Egypt and Libya. The Cushitic language is a branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family, and I use asaramaa to represent the month of July.

.

@etashelinto

@etashelinto