Keep Your Head

Inside John Williams's Stoner

Dear you, it’s half past ten and you’re seated on your bed, taking in the smell of the harmattan breeze, the sound of a neighbour’s generator, the ins and outs of your breath as you press pause for the day. You tell yourself that you’re well, even though the past few weeks have been a blur. Only the past few weeks. Not the many months you’ve stared blankly at life as it yawned over you. Not the repeated sleepless nights moulded by a wandering mind. Not the one-year-long relearning of self and life that’s shrunk (and continues to strain) your energy levels. Only the past few weeks. You are well.

You watch the darkness outside your window for a moment and wonder how exhausted the days and nights must be from their everlastingness; how they get by without a moment of rest, keep circling without a stop sign for refreshment. That’s suffering. But then all of life is suffering. The bird whose nest is uprooted by a storm. The fight against the fangs of inequity and inequality. The figuring of one’s path throughout all stages of life. The loss of a beloved, of the self, of a home. Shevek in Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia put it best when he said:

All of us here are going to know grief; if we live fifty years, we’ll have known pain for fifty years. And in the end we’ll die.

That’s a non-negotiable condition in our contract with life. To the young and old, the rich and poor, the wise and unwise, the ill and well, the giver and taker, all fated for a life toggling between pain and joy and the spectrum of emotions within us — some of which remain unnamed.

As you sit there, looking out your window, you release a sigh because this truth is an inhale and exhale; a bittersweet relief from the translucent image of these past few weeks. You let out the weight on your chest as Craig Armstrong’s Greenlight thins the darkness to a dot. You sit still as the seconds tick by and Birdy’s unbroken comes on and she asks:

Could you keep your head up

When you’re losing ground?

Though destined for pain, we’re required to walk around with hope in our aura. Hope carried by courage. Courage to be our ‘best selves’ even when we’re drowning. We’ve designed a culture in which an inquiry into another’s well-being is but a greeting. How are you? is a question waiting for a smile in response. Of course, we can’t go around feeding everyone our shadows. That’s too much weight on another, even an avenue for more pain should they choose to pit your shadow against you. But then:

Could you keep your head up?

If:

Everything you once loved

Like your own blood

Comes crumbling down

Could you keep your head up?

Sometimes the tears we cry

Are more than any heart can take

We hide, just keep it inside

Small wonder that it starts to break

How do you keep your head?

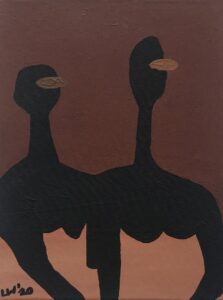

INSTIMBI, Lulama Wolf. 2021. THK Gallery.

In Stoner, John Williams tells the story of a man whose life telescopes us into the human reality of finding and losing love.

The book starts with a stark reminder of that final loss we acquire after death; how we slip from the memories of those with whom we shared space while living and ultimately evaporate from the minds of future generations. Willams writes:

When [Stoner] died his colleagues made a memorial contribution of a medieval manuscript to the University library. This manuscript may still be found in the Rare Books Collection, bearing the inscription: “Presented to the Library of the University of Missouri, in memory of William Stoner, Department of English. By his colleagues.”

An occasional student who comes upon the name may wonder idly who William Stoner was, but he seldom pursues his curiosity beyond a casual question. Stoner’s colleagues, who held him in no particular esteem when he was alive, speak of him rarely now; to the older ones, his name is a reminder of the end that awaits them all, and to the younger ones it is merely a sound which evokes no sense of the past and no identity with which they can associate themselves or their careers.

Untypical and awkward, Stoner falls in love with literature after leaving his rural farm—his old life, his parents—for the University. He’d gone in for agricultural science but would spend the rest of his life studying and teaching art and philosophy, subjects that connect us with the world and ourselves. He would go on to experience love in other forms of relationships: his (almost) friendship with David Masters and Gordon Finch, his marriage to Edith Elaine Bostwick, his time spent with his daughter, and his relationship with Katherine Driscoll.

But as present as love is the loss that accompanies each experience. Masters dies at war and Stoner’s relationship with Finch, who survives the war, becomes more of friendliness than friendship. The light between him and Edith disappears as quickly as it was ignited. And he withdraws into himself when two important figures in his life—his daughter and his role as a teacher—are taken away from him. Williams writes:

Time dragged slowly around him.

He came to feel that his presence was an embarrassment both to his friends and his enemies, and so he kept more and more to himself.

He found himself wondering if his life were worth the living; if it had ever been.

He took a grim and ironic pleasure from the possibility that what little learning he had managed to acquire had led him to this knowledge: that in the long run all things, even the learning that let him know this, were futile and empty, and at last diminished into a nothingness they did not alter.

During that year, and especially in the winter months, he found himself returning more and more frequently to such a state of unreality; at will, he seemed able to remove his consciousness from the body that contained it, and he observed himself as if he were an oddly familiar stranger doing the oddly familiar things that he had to do. It was a dissociation that he had never felt before; he knew that he ought to be troubled by it, but he was numb, and he could not convince himself that it mattered

He was forty-two years old, and he could see nothing before him that he wished to enjoy and little behind him that he cared to remember.

And when his relationship with Driscoll comes to an end, Stoner falls into an illness unlike any in his life. Theirs was a raw, sensual bond that hushed the rest of the world and opened them to each other. So, it’s unsurprising that Stoner should be so distraught when their time together dissolves. But what’s most notable about this interplay between love and loss is how Stoner keeps his head with literature, his first love.

In the summer of 1937 he felt a renewal of the old passion for study and learning; and with the curious and disembodied vigor of the scholar that is the condition of neither youth nor age, he returned to the only life that had not betrayed him.

[…]

The years immediately following the end of the Second World War were the best years of his teaching; and they were in some ways the happiest years of his life.

He worked harder than he had ever worked; the students, strange in their maturity, were intensely serious and contemptuous of triviality.

He knew that never, after these few years, would teaching be quite the same; and he committed himself to a happy state of exhaustion which he hoped might never end. He seldom thought of the past or the future, or of the disappointments and joys of either; he concentrated all the energies of which he was capable upon the moment of his work and hoped that he was at last defined by what he did.

His return to literature and fixation on teaching reminds us of our inability to stand still when all parts of our lives are unstable. We live in an uncertain world, one in which it’s easier to get by with at least one aspect of our life—social, mental, physical, financial, spiritual, or professional—in order. A healthy social circle can serve as a shelter during times of financial lack. Religious faith can buffer our mental pains. Career success can blunt our social vacuums. Abundance in one area of our lives acts as an anchor, a shield from the emptiness presented by lack.

THE EXCURSIONISTS, Lulama Wolf. 2021. THK Gallery.

Williams, among the roster of messages in Stoner, suggests that we can keep our head through love; the kind that’s sketched from within and, though threatened, will always remain ours, will always remain a long corridor through which we walk. Breakable but unsinkable. Flammable but not deletable. Bendable but firm in its foundation. Anyone who understands this love knows that it’s ever present. We may recoil from it when everything feels heavy, but we always return, we make our way back to it because it’s the best match for our suffering.

Williams also seems to suggest that this love is that which we find during a season of loneliness and discovery of self. It makes sense because loneliness is the hand that offers you different sources of oxygen, allows you to try them all, shows you which is best for breathing, and demands that you decide which you’ll keep. For Stoner, it was literature, a love he discovered during a season of aloneness and figuring. For me, it’s creativity—publicly expressed through Strange Notes, Letters of Consolation, and several other forms of creative work; privately expressed through fine arts and my approach to cooking or journaling or home decor. It’s where I place my feet when the earth chooses to unearth itself. It’s how I converse with myself, make room for vulnerability to speak its truth, and connect with that within and outside my body (and reality and realm).

It’s a kind of madness, this love. To hold space for something that doesn’t fit the conventional idea of what’s lovable. To know that it’s not a living being capable of embracing us when we need an arm’s warmth. To surrender our aliveness to something that cannot be held constitutionally accountable for our demise. Still, we keep our head in (and through) it because it teaches us what we are. It sees us. And what is love if not being seen and still held?

Could you keep your head

When you’re losing ground?

Could you find a daydream

In the dead of night?

You can keep your head. You should keep your head.

Many moons will light up the way

As sure as night will follow a day

And everything you once loved remains

Unbroken, unbroken

How will you keep your head?

The Big Question

Stoner is a book that ignites several questions about love, loss, and loneliness. How do you mourn someone that’s still alive? What does it mean to have parents but not know how to parent? How did people live through trauma at a time when mental health was given too little attention? Is it cheating if both partners do not love each other? How do you keep your head when it all turns chaotic?

As you think through these questions, here’s what you should read next: a prescription for loving yourself. Living through discomfort. The difference between love and addiction.

@etashelinto

@etashelinto