What is Content Anyway?

Unearthing the basics

One of my English teachers liked to say that there’s nothing new under the sun. “We had birds before post offices became a thing,” she’d say, dramatizing wildly with her hands. “We rode horses before cars and even told tales by moonlight before writing books. You see, different vehicles, same function.”

I’d forgotten all about her lessons until I deep-dived into AI writing tools and found that, throughout history, evolving media technologies have changed how we connect, receive information, and respond to changes in our environment. We’ve moved from relying on town criers to having the news on our palms, from experiencing music and drama on stage to having them plugged in our ears, from waiting days for messages to receiving them in seconds, from distant sources of information to more accessible media held together by the world wide web, the internet — which has not only redefined media consumption but narrowed the avenues for creative expression, turning large swaths of consumers into producers and potentiating the $104 billion creator economy that has injected the word content into our everyday lexicon.

From TikTok videos to blog posts, content pieces have become a staple in our everyday lives. We create, consume, and invest in them; and use them to inform, educate, persuade, and entertain. Yet they remain the only consistent but rarely—if at all—defined element of the media evolution.

So, What is Content?

Merriam-Webster sums up content in two simple words: something contained. Examples? Water in a bottle. Flower in a vase. Words in a book. Wax in your ear. Pasta on a plate. Cloves in a spice jar. Pupils in your eyes. Threads in a dress. Lines on your palms. Phlegm in your throat. A bean in a pod. Paint in an art piece. You get the gist.

These aren’t typically what we refer to as content. They’re not videos, articles, pictures, infographics, or any other content piece on the web. But the definition, something contained, provides a bare-bones understanding of content. It tells us that, at its core, content is any material that gives meaning to another material. A plate is useless without food (or water or paint or whatever else we use plates for). A drawer is merely an empty box without keys, notepads, underwear, jewelry, etc. The sky is (god knows what) without the clouds and the gases it holds.

When it comes to content on the internet — which is our core focus here —, Webster’s definition tells us, as they do in another section, that content is the “principal substance (such as written matter, illustrations, or music) offered by a website [or brand or group or person]. A YouTube channel is only another account on the internet without videos. Music is simply sound without rhythm. A blog is, well, not a blog without written pieces. And, actually, the internet is nothing without everything delivered through it.

I first thought about content as any information created and shared to inform, inspire, educate, or entertain its recipient. This definition is, of course, not novel. Margot Lester defined it somewhat similarly in 2011, Joe Pulizzi in 2013, and Karolina Niegłos in 2020, and it made sense to me until it didn’t because;

- To inform, educate, inspire, or entertain are only umbrella reasons for the numerous intentions behind different content pieces.

- The words, shared and recipient, suggest that for content to exist, it must always be distributed. But we know that content is sometimes left unshared by its creator, and that doesn’t reduce its significance. Also, activities like shared (Aka delivery) are secondary. Definitions are primarily about the what, not the how. This is also true for content.

With these, I refined the meaning of content to any material created for a specific purpose. But there’s another problem with this definition. The word, specific, implies that the goal behind a piece of content is always precise. In reality, though, our desired outcomes range from nonspecific plans like write and share articles to detailed objectives like write 1 case study and an ebook guide titled “essential robots to buy for your home” to attract ten leads by August 10, 2022.

So, what then is content?

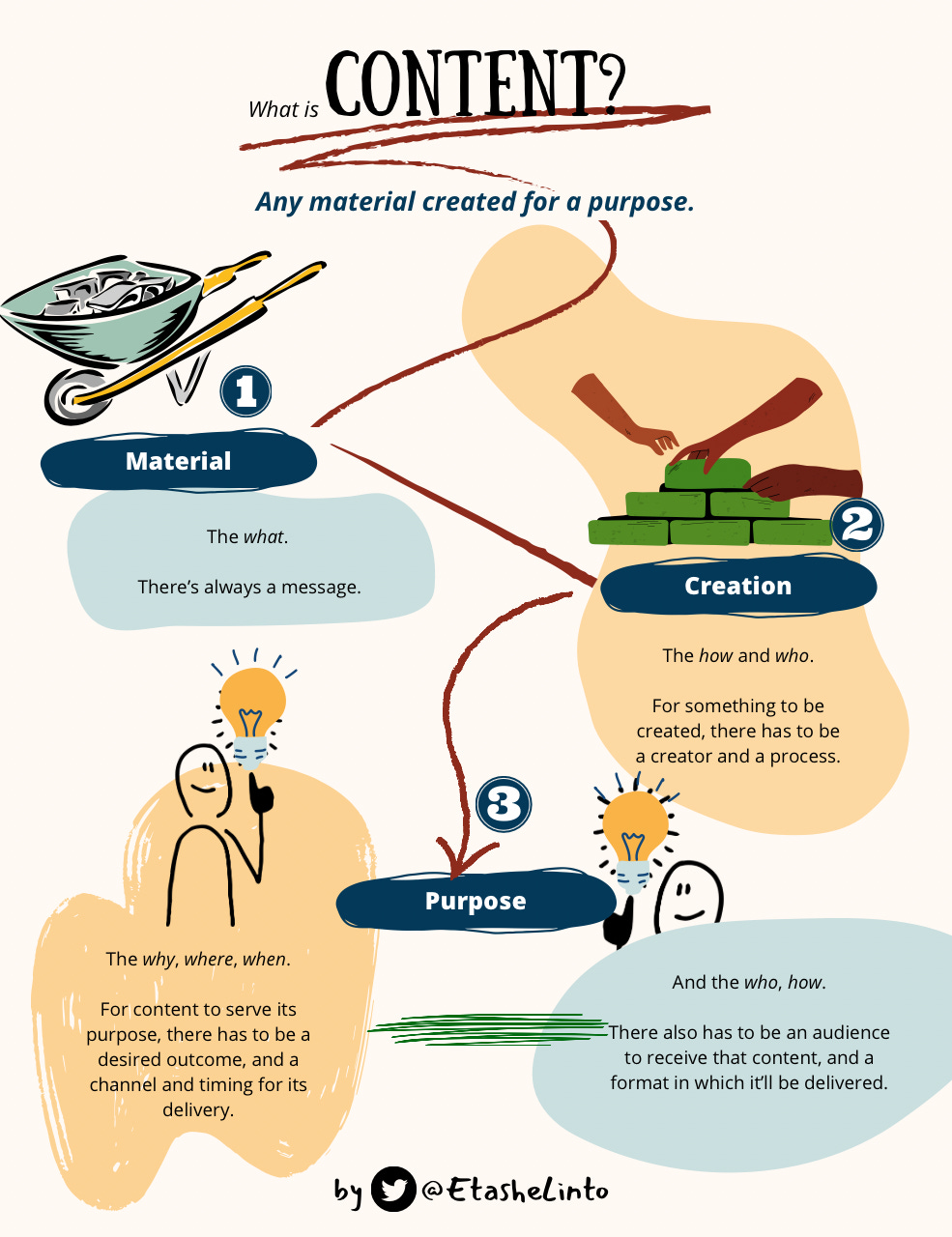

Content is any material created for a purpose

I asked around in a LinkedIn poll and 67% of nine respondents also thought of content as any purpose-driven material. Maybe because they understand that a piece of content without a why is like a business built on vibes.

It seems like a stripped-down definition, I know. And that’s the point here because when we understand its fundamental meaning, we then know how to apply it to specific themes, events, or industries. This definition reveals three essential components of content: material, creation, and purpose. It tells us that there’s always a what (the material), a who and how (for something to be created, there has to be a creator and a process), and a why, where, when, with another set of who and how (for content to serve its purpose, there has to be a desired outcome, a channel and timing for its delivery, an audience to receive that content, and a format in which it will be delivered).

The Raw Ingredients of Content

500 hours of video are uploaded on YouTube every minute. In 2021, 825 million books were sold in the U.S. alone, and over 48 million podcast episodes were published globally. We spend about 2½ hours per day using social media, and that’s only one source of media on the internet. While we typically regard these as content, we understand now that content pieces are essentially not defined by their format. They’re bodies of work housing a material, created through a process, and made for a purpose. The absence of these components renders content inexistent.

The Material

When Khabane Lame published his first videos on TikTok, they were of him dancing, performing comedy stunts, and showcasing other facets of his life, all in Italian. Months later, he began sharing his reaction to lifehack videos on the internet, shrugging and expressing exasperation at complex how-tos with otherwise simple solutions. And he’s not alone. In another part of Europe, TheMjWay shares videos expressing the same sentiment. But, while Lame speaks volumes without words, TheMjWay reacts with comments and a peal of laughter. Still, they both share the same message that resonates with millions around the world, showing us that the material of any piece of content is its message.

“I thought of a way to reach as many people as possible,” Lame told Faith Karimi and Gianluca Mezzofiore in a CNN feature, “and the best way was not to speak.” Calling it a “global language” in a New York Times profile, Lame understood early on that a piece of content is nothing without a message, and a message can be delivered in different ways — verbally or nonverbally, with words (and) or body language, as videos or articles or illustrations or audio recordings or a mix of all. This message is what Webster means by defining content as something contained. It is the substance, the subject matter of any piece of content, first formed as an idea and powered by a desired outcome.

A strong message is clearly defined, and a clearly defined message has a set purpose, which differs for each person and explains why we measure results differently. But having a set purpose doesn’t always mean that your message will be effective. We’ve all had the experience of sending out a social media post for visibility and getting too little or no engagement. It’s frustrating, and there are several reasons for it: Messages can fail when driven by an unclear purpose, communicated poorly, influenced by algorithms, or delivered at the wrong time, in the wrong place, or to the wrong person. The material of a content piece is its message, and effective messaging is first determined by clarity (of purpose) and then strengthened by its presentation, destination, and timing.

The Creation

To create is to bring an idea to life by deciding how our message will be crafted and presented to an audience. It requires action and differs according to our available resources, the systems we use, and whether we’re creating as a team or an individual.

For instance, the prolific writer, Maya Angelou, only used resources like a bed, a Bible, a dictionary, an ashtray, a bottle of sherry, Roget’s Thesaurus, and yellow pads. Her process entailed renting a hotel room for a few months, leaving home at six, and trying to be at work by six-thirty. “To write,” Ms Angelou told George Plimpton in a Paris Review interview, “I lie across the bed, so that this elbow is absolutely encrusted at the end, just so rough with callouses. I never allow the hotel people to change the bed, because I never sleep there. I stay until twelve-thirty or one-thirty in the afternoon, and then I go home and try to breathe; I look at the work around five; I have an orderly dinner—proper, quiet, lovely dinner; and then I go back to work the next morning.” But a team, like a film crew or marketing department, will use more resources and complex systems to bring a material to life. Regardless, a piece of content cannot be made without resources (like people, data, hardware, and digital tools) and systems (aka processes).

While resources enable creation, systems, as James Clear explained in Atomic Habits, are “best for making progress.” We can source the right resources, but the best systems — especially for teams — are designed, tested, and continuously refined.

The Purpose

We all have an intention behind the content we produce. We might make YouTube videos to share our worldviews, write sales letters to increase revenue, send out tweets to spark debates, create newsletters to build community, write cover letters to convince recruiters, and produce other types of content intended for different outcomes.

This intention is our why, the desired outcome of our content piece. It could be specific (grow Twitter presence to 5k followers) or nonspecific (increase Twitter following), singular (grow newsletter to 1000 subscribers in Q1) or part of a whole (generate 100 leads by gaining 1000 new email subscribers in Q1), engineered (work with top-level marketers and psychologists to design viral regional campaigns) or left to luck (follow a marketing trend and hope it goes viral). Regardless, our intention guides our actions.

For content to serve its purpose, there has to be a desired outcome, but also a channel for delivery, an audience to receive that content, and a format and time in which it’ll be delivered. A strong purpose is one that is clearly defined and personal to our brand or project. And although it doesn’t guarantee success, it informs the steps we take at all stages of our content efforts. It enables us to produce valuable content and gives us a way to measure the outcome of our work.

Leading With the Basics

In an article on first principles thinking, Shane Parrish and his team explain the difference between analogy and first principles reasoning with a fitting example. Quoting Tim Urban, they write: it’s like the difference between the cook and the chef. The chef is a trailblazer, the person who invents recipes. He knows the raw ingredients and how to combine them. The cook, who reasons by analogy, uses a recipe. He creates something, perhaps with slight variations, that’s already been created.

The material, creation, and purpose, are the raw ingredients of content. We can devise hundreds of messages, use various resources and systems to create them, distribute them to diverse audiences, whenever we want, through multiple channels, and do it all for different desired outcomes. But none of it matters if we don’t understand the muscles behind a piece of content. Doing so allows us to ask better questions as we create, pursue more worthwhile projects, and construct personalized methods for content creation.

@etashelinto

@etashelinto