Why is Everything so Uncertain?

A Strange Note in ⴼ*

In a portion of the deeply enriching classic, Love’s Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy, the existential psychiatrist, Irvin D. Yalom, explains that our desire for meaning is an innate pursuit providing us with ‘a sense of mastery: feeling helpless and confused in the face of random, unpatterned events, we seek to order them and, in so doing, gain a sense of control over them. Even more important, meaning gives birth to values and, hence, to a code of behaviour: thus the answer to why questions (Why do I live?) supplies an answer to how questions (How do I live?).’

It is no surprise, then, that when deprived of its sense of control, our being coils into the crevices of uncertainty, an experience that uproots our stability, threatens our sense of normalcy, and cripples our fortitude for moving forward. But in this age of abundant information; one where data is constantly mined and employed to predict outcomes and improve our decision making, how is it that we still get thrown into the void of uncertainty? Why is everything so uncertain?

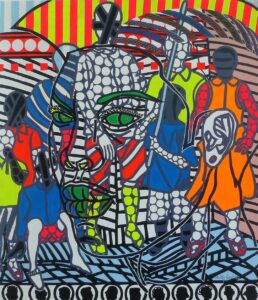

Bleeding sun by Paul Onditi. Via MONTAGUE CONTEMPORARY

Uncertainty is an all too common experience that rises from the crisis of loss; either of hope, relationships, a job, or – more disorienting – the self. Crisis encapsulates us in the particles of flight and fight, swallowing our knowledge and consuming our senses. And because we have a hard time accepting anything that overwhelms us, we beat our thoughts with mortars of unkind words and embrace the companionship of worry; we break vessels of tears and summon life to adorn us with its wings of grace. But too often, in our urgent desire for stability, we forget that the universe is in a constant state of motion, and so ‘there is a contradiction in wanting to be perfectly secure,’ as the poet, Alan Watts, beautifully observed, ‘in a universe whose very nature is momentariness and fluidity.’

Uncertainty exists because life is fluid, and we cannot tell the future. In her documentation of understanding the line between luck and human efforts, the writer and psychologist, Maria Konnikova, reminds us in The Biggest Bluff that the thing about life is ‘You can do what you do but in the end, some things remain stubbornly outside your control.’

Real life is not just about modeling the mathematically optimal decisions. It’s about discerning the hidden, the uniquely human. It’s about realizing that no amount of formal modeling will ever be able to capture the vagaries and surprises of human nature.

Beyond being a product of life’s fluidity and our mortality, uncertainty arrives when we do not have complete information, which leads us into the cliffs of mistake and flings us to a place of crisis where we easily forget, as Richard Diebenkorn observed in a record of his journey as an artist, that ‘mistakes can’t be erased, but they move you from your present position.’

Upon its arrival, uncertainty transports us into the darkness of fear and impedes our capacity for observation, such that we become unable to hear the voice of the universe. Through her self-experiment with poker, Konnikova observes that ‘when this fear comes in, we can’t hear the message of the universe because our emotions are at their peak when we are afraid. We end up not thinking clearly. We end up only being on the lookout for what we desire (wishing chance to bend to our will) and missing the other message it might be trying to tell us with the information around us.’ And so it is important to see that in granting access to the unknown, for our transformation, we are not necessarily called to change our vision, but to perceive the lessons acquired in our time of crisis and the other ways we can become.

Still, our inability to hear the universe is not entirely our fault. It is a problem of evolution. As Konnikova exposes, ‘The equation of luck and skill is, at its heart, probabilistic. And a basic shortcoming of our neural wiring is that we can’t quite grasp probabilities. Statistics are completely counterintuitive: our brains are simply not cut out, evolutionarily, to understand that inherent uncertainty. There were no numbers or calculations in our early environment — just personal experience and anecdote.’

With this understanding that life is an ever-changing journey in which our mortality lacks control of the unknown, with this knowledge that uncertainty springs forth from crisis, which is an unrelenting component of our existence, with this revelation that our biology bears a hand in our inability to hear the universe when in crisis, how, then, can we live through uncertainty?

Les marabouts by Boris Nzebo. 2019. ARTX

Antidotes for Uncertainty

The self, through a trove of influences, is constantly being transformed into newer versions of being. Uncertainty is one of such influences that shifts the course of our existence. And underneath the fear ejected by uncertainty lies a chance to live as a different self (either as we take on a new career path, walk away from an abusive environment, let go of an addiction, or attempt other ways of living).

Life is a journey. As with every journey, we pass through an array of environments amidst fluctuating climates. And so when walking through the surroundings of uncertainty, we are called to get comfortable with the unknown; to embrace phrases like ‘I don’t know’ because they unlock the unexplored portions of life; to breathe in the discomfort of uncertainty because, after all, certainty may or may not come later and uncertainty is an everlasting experience, only changing its driver at different stages of our lives.

In Love’s Executioner and Other Tales of Psychotherapy, Yalom admonishes that ‘the capacity to tolerate uncertainty is a prerequisite [for getting through it]… The powerful temptation to achieve certainty through embracing an ideological school and a tight therapeutic system is treacherous: such belief may block the uncertain and spontaneous encounter necessary for effective therapy.’

In our walk through uncertainty, we are also called to approach the future in stages. Too often, in our attempt to escape the weight of uncertainty, we aim toward utter clarity for the far future, rather than uncovering the next best step. But as the scientist, Carl Sagan, observes in The Demon Haunted World, ‘humans may crave absolute certainty; they may aspire to it; they may pretend, as partisans of certain religions do, to have attained it. But the history of science — by far the most successful claim to knowledge accessible to humans — teaches that the most we can hope for is successive improvement in our understanding, learning from our mistakes, an asymptotic approach to the Universe, but with the proviso that absolute certainty will always elude us.’

1 Question for You

How do you respond to uncertainty?

As you think through this question, here’s what you should read next: Digest scribblings on the complexity of free will. Revisit the lessons of identity and being as multiple selves. Close with a detailed exploration of The Biggest Bluff.

*ⴼ is the Tamazight letter for the alphabet, F. Here, ⴼ is used to represent the month, June. Tamazight is a member of the Berber language, which is classified as an Afroasiatic language. Tamazight is spoken in the Atlas mountains in central Morocco by over 4 million people. ⴼ iS a Neo-Tifinagh alphabet in Tamazight, which is also written with the Arabic script, and the Latin alphabet.

@etashelinto

@etashelinto